“The camera doesn’t lie” is often assumed to be true about historical photographs, even though we know that maxim is certainly not true in the twenty-first century. This phrase first began to be used in the late nineteenth century when new technology allowed photographs to be printed in books, magazines, and newspapers.

In the classroom, historical photos and videos appear to be more “honest” than other types of historical primary sources. Consider the following when asking students to analyze primary source photographs.

Photo: Early photography equipment [1864] / Library of Congress

1. The timeline of photography inventions matters

Digital photography revolutionized how we take, use, and view photographs and video, but this technology only became widely available about twenty years ago. Digital photography makes every person with a cell phone a creator of future historical primary sources. Students must understand what technology was available in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to take photographs and motion pictures and who did and did not have access to this technology. For example, the first photograph was taken in the 1820s. But it wasn’t until 1900, eighty years later, when average people could take their own snapshots with an inexpensive, mass-marketed camera called the Brownie. And even then, taking photographs was costly because of the need to purchase film and pay for the film to be developed and images printed on paper. Ask students to take this short, fun quiz highlighting key photography inventions.

Throughout the 1800s, photographs were taken by professionals. Therefore, nineteenth-century portraits are very different types of primary sources than twenty-first-century selfies. Ask your students to consider how they might dress differently for a formal portrait taken in a studio. How do you expect the outcome of a photo to be different if you are paying for it? Can everyone afford photographs by a professional photographer?

Ask students to analyze the types of snapshots, selfies, and videos they create in an average day or week. Then assign students a real person or persona from the past and ask them to consider how historical knowledge of that era would be different if we had these types of digital images as a historical record.

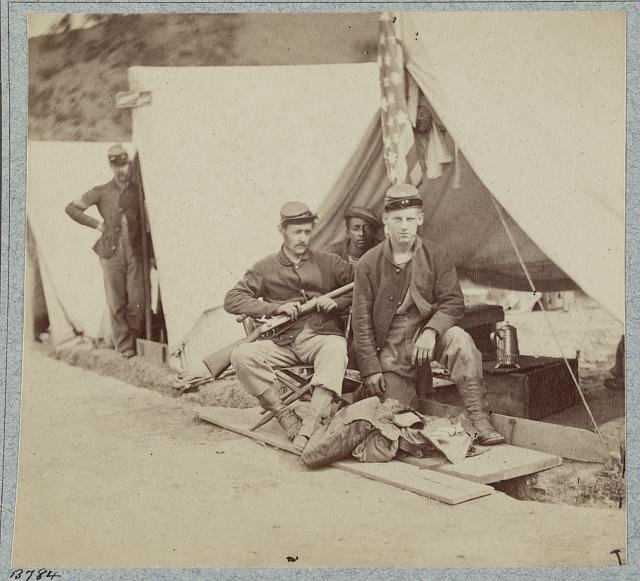

Photo: Matthew Brady Photography Collection [1861] / Library of Congress

2. Photojournalism has changed over time

In the 1840s, photojournalists started to cover major events. Mathew Brady’s famous photographs of the Civil War are the best-known example. However, bulky camera technology and complicated methods of printing photographs meant that many of these early news photographs were more like formal portraits than the action shots we expect today. It wasn’t until the 1920s and 1930s that compact cameras with flashbulbs enabled photojournalists to snap pictures of action while it happened.

As students analyze primary-source news photographs of an event from the nineteenth century, ask them to consider what photographs do not exist because of the limitations of photography technology of the time. How would the event be covered today with video or photographs? What types of images would we have from social media provided by average people with their digital camera phones? How does coverage of news by individual people tell a different story than coverage by a few professional photographers and newspapers?

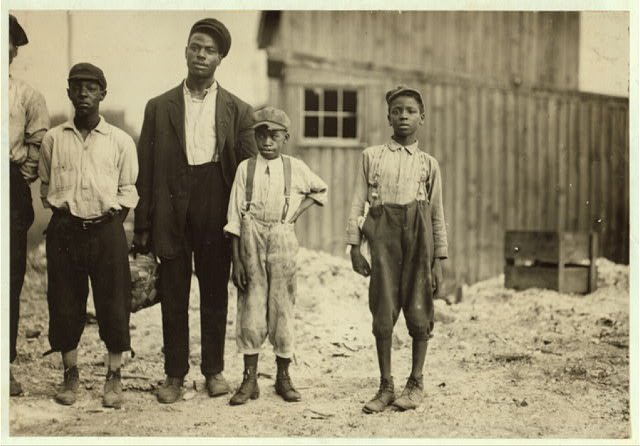

Photo: Lewis Hine [1911] / Library of Congress

Photo: Lewis Hine [1911] / Library of Congress

3. Even early photographers had agendas

We’ve all seen the famous photographs of child labor and urban poverty from the early twentieth century by Lewis Hine and Jacob Riis. The most common photographs depicting the Depression and World War II in textbooks were taken by the Farm Security Administration and the Office of War Information. These government agencies and photographers had agendas. Students must understand that agendas or biases are not automatically bad things. All of these photographers were taking photographs for what most considered a good cause: to highlight the evils of poverty and child labor or to highlight the achievements of Americans during war. However, knowing who took a photograph and why is just as important for modern photographs as well as images from the past.

Recommended resource: Examining the Evidence: Seven Strategies for Teaching with Primary Source, by Hilary Mae Austin and Kathleen Thompson, provides excellent additional information and strategies for analyzing primary source images.

Want additional resources to enhance primary source analysis skills?

Try a free Active Classroom 30-day trial.

Cynthia W. Resor is a social studies education professor and former middle and high school social studies teacher. Her dream job? Time-travel tour guide. But until she discovers the secret of time travel, she writes about the past in her blog, Primary Source Bazaar. Her three books on teaching social history themes feature essential questions and primary sources: Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries: Modern Lessons from Historical Themes; Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies and Exploring Vacation and Etiquette Themes in Social Studies.