Education has always been a powerful tool for empowerment and social change, and throughout history, and educators and social activists have played pivotal roles in shaping opportunities for future generations. These five influential female figures have not only advanced educational access but also redefined what education can look like in America and across the globe.

Education has always been a powerful tool for empowerment and social change, and throughout history, and educators and social activists have played pivotal roles in shaping opportunities for future generations. These five influential female figures have not only advanced educational access but also redefined what education can look like in America and across the globe.

Their legacies continue to inspire educators, students, and policymakers today. We celebrate them for Women’s History Month in the month of March.

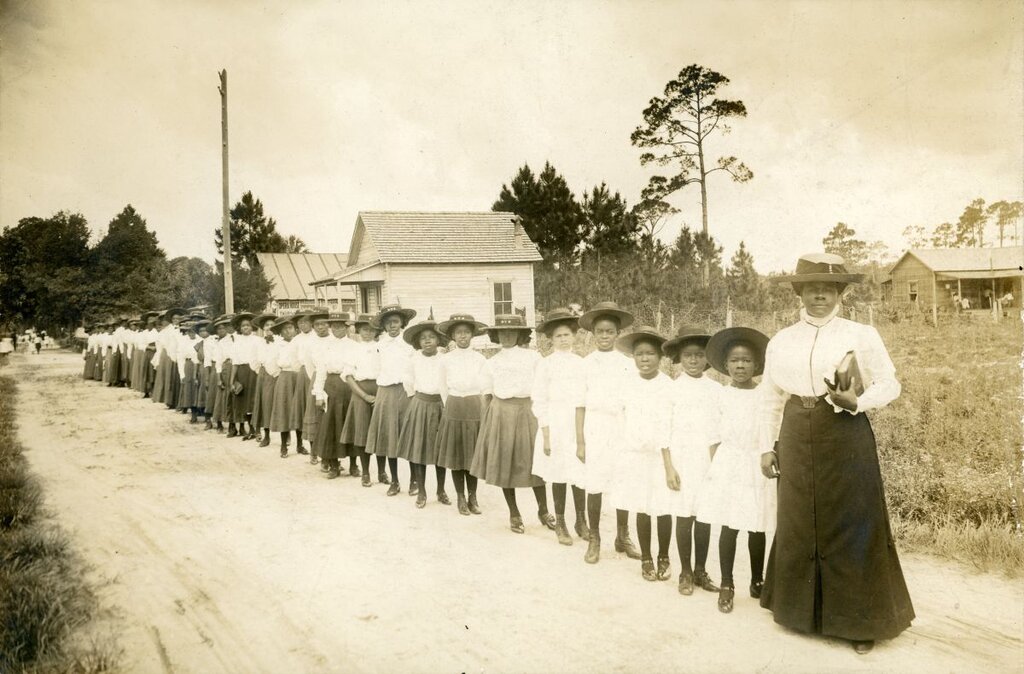

Mary McLeod Bethune (1875–1955)

Mary McLeod Bethune was a trailblazing educator, civil rights leader, and advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. She believed that education was the most effective way to empower the Black community. In 1904, she founded the Daytona Educational and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls in Florida, which later merged with the Cookman Institute to become Bethune-Cookman University, one of the nation’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs).

Bethune’s influence extended far beyond the classroom. As the founder of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW), she worked tirelessly to advance the rights of African American women. She was also a key member of FDR’s unofficial “Black Cabinet,” advising on issues of racial equality. Bethune’s philosophy emphasized self-reliance, racial pride, and the importance of education in achieving social and economic progress. Her work laid the groundwork for future civil rights and education advancements and continues to inspire leaders today.

Maria Montessori (1870–1952)

Born on August 31, 1870, in Chiaravalle, Italy, t a time when higher education for women was rare, she became one of the first female physicians in Italy, earning her medical degree in 1896 from the University of Rome. Initially, she worked in psychiatry, focusing on children with disabilities, which sparked her interest in education. While working with children in asylums, Montessori observed that they responded better to hands-on learning than traditional rote memorization.

In 1907, she opened her first classroom, Casa dei Bambini (Children’s House), in a poor neighborhood in Rome. Here, she introduced child-sized furniture, hands-on learning materials, and an emphasis on choice and independence—all revolutionary ideas at the time. The success of this classroom led to worldwide interest in her approach.

Montessori’s work spread rapidly, leading to the opening of Montessori schools across Europe and the U.S. She trained teachers worldwide and published several books, including The Montessori Method (1912), which remains a cornerstone of early childhood education. Montessori education is practiced globally in over 20,000 schools across countries, influencing early childhood education, special education, and even workplace learning.

Elizabeth Evelyn Wright (1872–1909)

Born in Talbotton, Georgia, Wright was deeply inspired by Booker T. Washington’s philosophy of industrial education. She attended the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where Washington himself mentored her. His emphasis on self-reliance and vocational training shaped Wright’s own vision for education as a tool for empowerment, particularly in the rural South.

Despite facing extreme racial hostility, including threats and the burning of school buildings, Wright was determined to provide educational opportunities for African American youth. In 1897, she founded the Voorhees Industrial School at just 23 years old, with the support of wealthy philanthropist Ralph Voorhees from New Jersey.

The school initially focused on industrial and agricultural training, equipping students with practical skills to improve their economic standing. Wright’s leadership helped lay the foundation for future generations of Black educators and professionals. Her legacy endures through Voorhees University, a prominent HBCU, which remains dedicated to fostering leadership, academic excellence, and social responsibility. Wright’s life is a testament to resilience, courage, and the transformative power of education.

Jane Addams (1860–1935)

Best known as a trailblazer in education, reform, and social work, Jane Addams was born on September 6, 1860, in Cedarville, Illinois. Her father, a wealthy businessman and state senator, encouraged her education, which was uncommon for women at the time. She attended Rockford Female Seminary, where she excelled academically and developed a passion for social justice.

After traveling through Europe, she visited Toynbee Hall, a settlement house in London that provided education and social services to the poor. This visit inspired her to establish a similar institution in the United States. In 1889, Addams and her friend Ellen Gates Starr founded Hull House in Chicago, one of the first and most famous settlement houses in the U.S. Hull House provided education for immigrants and working-class families (including English classes, history, and citizenship lessons), early childhood education programs, vocational training and job placement, as well as cultural and recreational activities (theater, art, and music programs).

Hull House was groundbreaking because it focused on hands-on, community-based learning, a principle that influenced modern adult education, early childhood education, and civic engagement programs. Jane Addams’ work laid the foundation for modern social work, adult education, and community-based learning. Hull House became a model for settlement houses across the United States, influencing policies in education, public health, and social welfare.

Elizabeth Peabody (1804–1894)

Peabody was born on May 16, 1804, in Billerica, Massachusetts. Raised in a highly intellectual family, she was exposed to literature, philosophy, and education from an early age. Her mother, a teacher, influenced her passion for education, and Peabody became a teacher herself as a young adult. She was deeply involved in the Transcendentalist movement, working with Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Margaret Fuller. She later opened a bookshop in Boston, which became a hub for intellectual and educational discussions.

Perhaps best known for introducing the first English-speaking kindergarten in the United States in 1860, she was inspired by Friedrich Fröbel, a German educator who founded the kindergarten system, which emphasized play-based learning, hands-on activities, and child-centered education. She promoted Fröbel’s ideas in America and trained kindergarten teachers, believing that early childhood education was crucial for moral, social, and intellectual development. Her work led to the widespread adoption of kindergarten in the United States. education system.

Peabody’s work helped shape modern early childhood education. Today, her influence is seen in the universal kindergarten system in the U.S., teacher training programs, and the emphasis on play, creativity, and child-led learning in early education.

Seeking more lessons to celebrate women and integrate multidisciplinary lessons all year round?

Sign up for a free 30-day trial of Active Classroom

This listicle has been created by the team at Social Studies School Service. It has been edited for clarity and length.