Determining whether voting is a right or a privilege has been a battleground for states to control who can cast a ballot in elections. Technically, states regulate eligible voters, but, through the course of history, the US federal government has made several key decisions that have altered those requirements in an attempt to create more equality in the voting process.

Closely looking at the history of voting in America helps to give context and shows how far the country has come in giving all citizens a voice—and how far we still have to go to ensure voting is a right, not a privilege.

Post–American Revolution

In the earliest days of our republic, the founding fathers sought to create a more perfect union with a new government and laws of the land. They saw voting as a fundamental component of democracy and added it into Article I of the Constitution, empowering state legislatures to oversee federal elections.

However, voting rights were exclusively granted to male freeholders, or those who owned property and paid taxes. Those men were overwhelmingly white, Protestant, and over the age of twenty-one, meaning that only a small subset of the population could vote. Just 6 percent of those in this new America were eligible to vote to elect the first president, George Washington, in 1789. All other residents of the newly freed United States remained ineligible.

Photo: iStock by Getty Images / mphillips007

The Fifteenth Amendment

After the Civil War ended slavery, Congress passed the Fourteenth Amendment to extend citizenship rights to freed slaves. This amendment directs that “no State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.”

While this legally granted citizenship rights to former slaves, this measure did not include the right to vote. It was not until the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment two years later that black men would be allowed a voice during elections. This amendment states that the “right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” However, although this expanded voting rights to black men in the South, politicians in the post–Civil War Reconstruction and Jim Crow landscape subsequently passed measures to suppress voter turnout of African Americans.

These tactics included making black voters pass literacy tests, mandating that voters pay a tax to cast a ballot, requiring a white person to “vouch” for a black voter, whites-only Democratic primaries in southern states, and outright voter intimidation and violence against African Americans at the polls.

Photo: Library of Congress

Women’s Suffrage

In 1848, prominent abolitionist activists such as former slave Frederick Douglass and women’s suffrage advocates Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton convened together, for the first time, in Seneca Falls, New York. The convention is now considered the birth of the women’s suffrage movement in the United States.

In 1872, Susan B. Anthony was famously arrested along with fifteen other women and prosecuted for attempting to vote in the presidential election. In the next several decades, the women’s suffrage movement surged.

Years of activism resulted in the historic passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the US constitution, prohibiting states from denying citizens the right to vote based on sex. Even though this was a monumental occasion for women, voting remained inaccessible for women of color for several decades afterward because Native American and Asian American women were often denied citizenship by the federal government.

Photo: Library of Congress

Photo: Library of Congress

The Voting Rights Act of 1965

After decades of hard-fought civil rights activism from leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and John Lewis, the landmark Voting Rights Act was signed into law, outlawing several racially discriminatory practices intended to keep people of color from voting. This act banned southern states from using literacy tests to keep African Americans from voting and also directed the Department of Justice to oversee voter registration efforts in counties where less than half the African American population was registered. The DOJ required that places with a history of discrimination obtain pre-clearance before implementing any new voting policies.

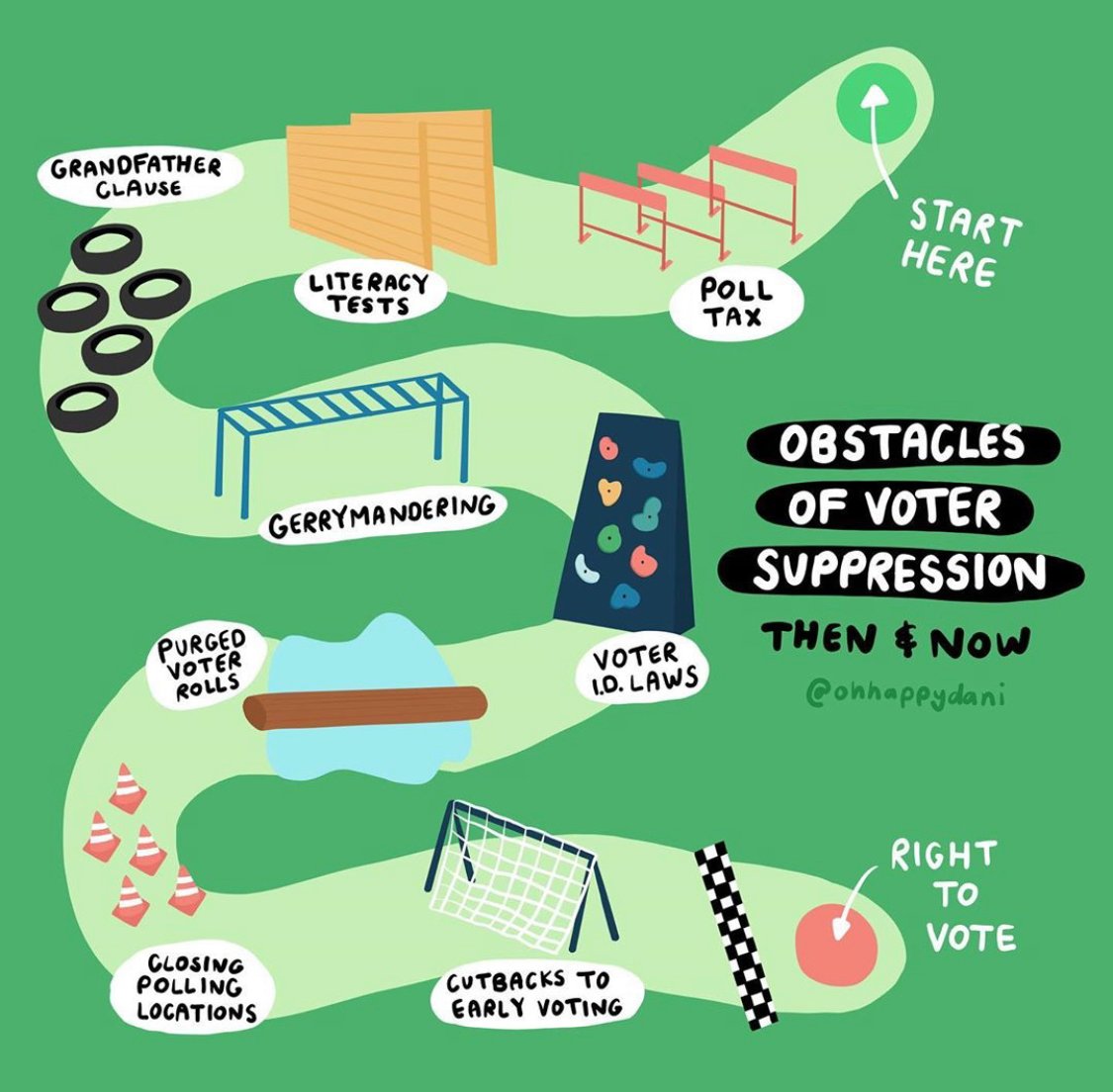

Photo: Instagram / @ohhappydani

Modern-Day Voting

In 1971, Congress voted to lower the federal age from twenty-one to eighteen with the passage of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment to the Constitution. The change was largely enacted because of young men who were drafted to fight in the Vietnam War, who argued that if they were old enough to go to war, they were old enough to vote.

In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of states in Shelby County v. Holder, striking down an important part of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The court ruled that Section 4(b), requiring states and local governments to obtain federal preclearance before implementing changes to their voting laws, was unconstitutional. Echoing the Jim Crow era, many southern states rushed to close or change polling locations and impose in-person voting policies and strict voter ID laws in the wake of the decision. Most prominently, North Carolina passed a comprehensive vote-restriction law that cuts back on early voting, restricts private groups from conducting voter-registration drives, eliminates Election Day voter registration, and imposes the strictest voter ID rules in the country.

In November 2018, voters in Florida approved a constitutional amendment overturning the state’s disenfranchisement law, allowing around one million formerly disenfranchised residents to vote. The following year, the Florida legislature passed a law that requires people with felony convictions to pay off any court fines and fees before they can register to vote, which critics say still discriminates against poorer residents. There is still an appeal pending against this state mandate.

So the debate remains: In America, is voting a right or a privilege? As a country, we have come a long way from only allowing land-owning white men the right to vote, but it is clear that measures to restrict voting are still in place. If history is any indication, all individuals deserve the right to use their voice and vote for individuals to represent their interests. Only time will tell what other changes will unfold in the voting debate.

Storypath: Elections can enhance student civic skills through simulation learning

References

https://www.sos.wa.gov/_assets/elections/history-of-voting-in-america-timeline.pdf

Monet Hendricks is the blog editor and social media/meme connoisseur for Social Studies School Service. Passionate about the field of education, she earned her BA from the University of Southern California before deciding to go back to get her master’s degree in educational psychology. She currently attends the graduate program at Azusa Pacific University pursuing advanced degrees in school psychology and Applied Behavior Analysis. Her favorite activities include watching documentaries on mental health and cooking adventurous vegetarian recipes.