Author’s mother, Addy Yolanda López de Moguel, quinceañera, 1961, Mérida, Yucatán, México.

It is time for the Cinco de Mayo celebrations again. This minor Mexican holiday has been relegated to being a regional American beer holiday, but it can also provide some teaching opportunities for your classroom.

In a time of political and social polarization in diverse classrooms, teaching about the physical but also political, economic, and social walls between the U.S. and Mexico, can produce tense, fractured discussions in the classroom. I have found that music helps. It entertains, soothes, and calms. But more than just making students feel better, it can make history interesting, accessible, and relevant to them. Even before being heard, it can begin to do so, with intriguing questions. Here is one of the more intriguing ones you may come across: Many Latino female students are preoccupied with planning their quinceañera celebration at around the time you are teaching them about a world war ignited by the assassination of an Austria-Hungarian royal. Why does their Latin American quinceañera celebration feature an Austrian waltz? And what do both have to do with Cinco de Mayo?

Music and history, maestro, please!

The Waltz and European Imperialism

The waltz arrived in Mexico sometime after the new country’s declaration of independence from Spain in 1810, and the condemnation of the dance as immoral and sexually suggestive by a conservative Catholic Church helped make it popular (Jímenez, 2002). It reached perhaps its greatest popularity in the time of the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz, before the Mexican Revolution of 1910 (Brust Hernández, 2010). The battle of Cinco de Mayo in 1862 took place almost exactly between those two points, and asking how music and dance and war could be related should get the attention of the anxious quinceañera and her friends.

Explore thousands of world history activities with a free trial of Active Classroom

A Quinceañera Opens Windows to History

European waltzes became considered folk music in Mexico because they have been played for so long in the country, adopted by indigenous communities, and produced melodies on which Mexican composers of classical music have built their work (Jímenez, 2002). At various points of Mexican history, political conservatives and clergy, shunning indigenous forms of expression and culture, have sought to replicate European ideals of monarchy and upper-class society. The Catholic Church, on its mission to convert the indigenous peoples to Catholicism, allowed Mexicans to continue the coming-of-age rituals they had inherited from indigenous peoples, but incorporated European elements. Parents modeled the quinceañera after the debutante balls of Europe, the celebration serving to display the prosperity of the family, and to introduce the girl to society and announce her availability for marriage. A Viennese waltz is a proper highlight of a day devoted to making a young girl feel like a royal princess.

The popularity of waltz music during the time of these interactions between European imperialists and Mexico can be partially credited to Johann Strauss II. Strauss became the greatest composer of the waltz for the elegant ballrooms of Europe. He had been born near Vienna, Austria, and began his composing and performing career at around the same time that the U.S. and Mexico were fighting a war over what is now the American Southwest (1868-48), and that the Austrian Empire in Europe was experiencing a revolution. The young Strauss eventually composed patriotic marches in honor of the Habsburg Emperor Franz Josef I, a smart political move, although he secretly supported the Austrian rebels.

European Imperialism in Mexico

From Mexican debt to the Monroe Doctrine to European monarchs in Mexico, these events in Mexican history explain a lot about the mixing of cultures that lead to the current iteration of the quinceañera.

Issues with Debt Collection Lead to Restored Monarchy in Mexico

Back on the American continent, after its defeat at the hands of an expansionist U.S., a weakened and young Mexico found its finances strained by internal civil war between conservatives and liberals (1857-60) and foreign debt to England, France, and Spain. In 1861 Mexican President Benito Juárez suspended foreign debt payments, leading to an alliance of England, Spain, and France planning to send a military expedition to Mexico’s major ports to collect debt payments by confiscating duties and fees imposed on exports/imports. The plan was to respect Mexico’s sovereignty and territory. The U.S. was invited to join the alliance, but declined to maintain positive relations with Mexico, but also possibly because it had become embroiled in its own Civil War. Negotiations resulted in diplomatic accords to resolve the dispute, but when France sent military reinforcements, it became clear that Napoleon III intended to join Mexican conservatives to overthrow the Juárez regime. England and Spain settled their claims with Mexico and recalled their troops, but France pressed ahead to occupy and restore monarchy to Mexico (Miranda Basurto, 1974).

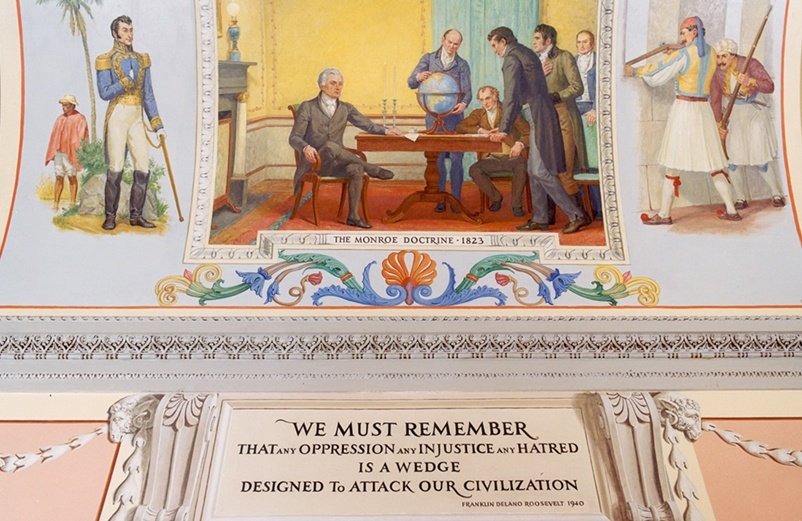

This creates an opportune segue to teach students about the Monroe Doctrine and how it relates to a more exciting topic: Cinco de Mayo. The U.S., weakened by its own Civil War, was unable to enforce the Monroe Doctrine it had declared back in 1823, promising to protect Latin America from European intervention. So France, whose glorious and inspiring revolution in the late 1700s had transformed into the Second Republic under Napoleon III, nephew of Napoleon I, waltzed into Mexico. In one of the first military conflicts, General Ignacio Zaragoza’s army and the people of Puebla defeated an army of French soldiers and Mexican conservatives on May 5, 1862–the battle commemorated by the Cinco de Mayo holiday.

Still more interaction between Europe and Mexico was in store. Mexico won the battle but lost the war, and France went on to increase the size of its army, working with Mexican conservatives opposed to the liberal President Benito Juárez, and after a 2-year occupation, installed Maximilian I as Emperor of Mexico in 1864.

Europeans Installed as Mexican Monarchs

Maximilian I was an archduke of Austria, the younger brother of Austrian Emperor Franz Josef I, the same one for whom Strauss composed marches and waltzes (Fuentes, 1992, pp. 270-275). Maximilian was living in exile in Trieste, Italy, and his brother saw him as a future rival for power and wanted him out of Europe. Napoleon III needed someone through which he could carry out his imperialist agenda in the New World. Mexican conservatives needed a European royal to wrest back their power in Mexico, and in fact had a plan for Napoleon III to select some other Catholic royal in case Maximilian declined. Maximilian was duped into thinking he had the support of a majority of Mexicans, agreed to give up his rights to the Austrian throne, and assumed the throne along with his wife Carlotta, daughter of Leopold 1, King of Belgium. The couple were essentially minor royals tapped to be puppets of more powerful others’ desires for power (Canto Lopez, 1975, pp. 477-506).

The European Puppet Show Ends, but the Dance Stays

When the United States’ Civil War ended in 1865, the U.S. was once again able to enforce the Monroe Doctrine and demanded that France withdraw from Mexico. When France faced a second threat of an ascendant Prussia, Maximilian lost the financial, military, and political support he had from his European backers. The Mexican liberals gained the upper hand and restored Benito Juárez to the presidency, and President Juárez had Maximilian executed. The puppet show was over. This might be a great way to talk to students about the longlasting effects of imperialism. Not only did the waltz stick around, what other longlasting effects, perhaps less innocuous, might have continued even after the imperialists left Mexico?

Use the Music to Teach History

It is sad that political, economic and ideological differences, and persistent racial and ethnic animosity, always obscure joyous social and cultural interaction between human beings. But with the aid of music, learning about these cultural interactions and contacts can help us better understand the conflicts, and perhaps bridge some and resolve others. As the great Mexican President Juárez once said, “Respect for the rights of others is peace.” It sounds better in Spanish, of course: “El respeto al derecho ajeno es la paz.”

Explore thousands of world history activities with a free trial of Active Classroom

References

Acknowledgment: The author would like to thank retired LAUSD principal Javier Miranda for the two references below from the University of Guadalajara, Mexico.

Brust Hernández, Lidia Esperanza (2010). Musical Forms of Mexican Folklore. University of Guadalajara, Center of Art, Architecture and Design, School of Plastic Arts, Santa Maria de Gracia Cloister. Guadalajara, Mexico. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

Canto Lopez, A. (1975). Historia de Mexico, 1517-1970. Mérida, Yucatán, México.

Fuentes, C. (1992). The Buried Mirror: Reflections on Spain and the New World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Jímenez, Gabriela (2002). Commentary originally appearing in El Universal, Monday, April 1, 2002. Quoted by Musical Forms of Mexican Folklore. University of Guadalajara, Center of Art, Architecture and Design, School of Plastic Arts, Santa Maria de Gracia Cloister. Guadalajara, Mexico. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

Miranda Basurto (1974). La Evolución de México. A course of study for middle schools in Mexico. México, D.F.: Editorial Herrero, S.A.

National Center for History in the Schools (1998). Duel of Eagles: Conflicts in the Southwest 1820-1848, A unit of study for grades 8-12. Arevalo, J., Drake, J., Sesso, G., and Vigilante, D., authors. Los Angeles, CA: National Center for History in the Schools, UCLA.

Sheehy, D. E. (2009). Introduction to Los Texmaniacs: Borders y Bailes. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, Latino Initiatives Pool, Smithsonian Latino Center.

David L. Moguel is a professor of teacher education at the Michael D. Eisner College of Education, CSU Northridge. He holds degrees from Stanford University, the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, and UCLA. David served as a John Gardner Public Service Fellow with Ramon C. Cortines, school superintendent, and as a presidential management intern for the U.S. Department of Education. He is the co-author, with Ron Sima, of Teach Me, I Dare You: Taking Up the Challenge of Teaching Social Studies, published in 2011 by Social Studies School Service.