Going viral is the rapid spread of information, not diseases. The phrase entered the English language in the late 1980s and is usually associated with the internet, email, or social media but can also refer to information spread by word of mouth.

The term going viral in electronic media is only a few decades old, but the concept is not a new thing. Information—accurate and inaccurate—spread wide and far to audiences in previous centuries just like it does today with the internet. Examining how this happened in the past highlights three key issues for teaching media literacy. First, popularity may or may not equate accuracy; second, tracking the source of information can be challenging; and third, understanding how information is distributed helps one better assess the message.

Information Exchange at the Turn of the Century

In the nineteenth century, newspapers and magazine editors used “exchanges” to gather new information. Editors exchanged subscriptions with other publications from across the nation and reprinted information for free. The US Post Office allowed these exchanged publications to be mailed at no cost. This system was especially valuable to small-town newspapers with small staffs; they could share news, poetry, fiction, practical advice, interesting facts, and opinions from across the nation with their readers at no cost.

At the time, copyright laws did not apply to periodical publications, and editors were not required to seek the permission of the author. Sometimes the source of the information was cited, but often it was omitted or changed to appeal to the audience of the publication. Historian Ellen Gruber Garvey notes that the 1863 poem “Mortally Wounded,” about a dying Civil War soldier, was reprinted with varying attributions, making it equally popular in both the North and South.

“Going viral” in nineteenth-century print publications was a slower process than reposting, retweeting, “liking,” and email forwarding in the twenty-first century. However, the effect was similar. Then as now, people from across the nation and world read and were influenced by the same information or disinformation. Questioning the content, author, and purpose of popular content was and is essential.

Source: Library of Congress

Interesting Statistics

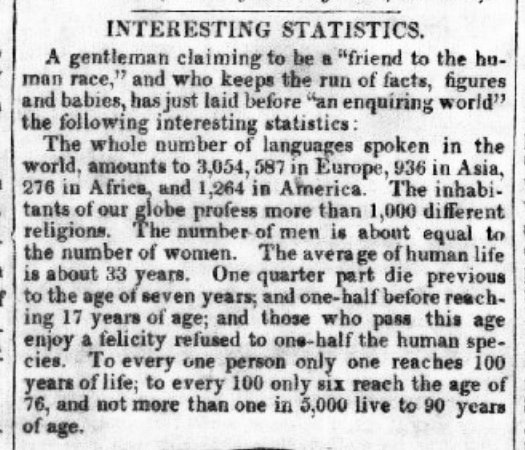

The nineteenth-century example of viral information below provides a perfect opportunity to practice both primary source analysis and media literacy skills. “Interesting Statistics” was published in dozens of newspapers between 1836 and 1860. When an author was identified, he was only described as “a gentleman claiming to be a ‘friend of the human race.’” In some of the versions, another newspaper was cited at the end of the article. In others editions, no source was cited.

“A gentleman claiming to be a ‘friend of the human race,’ and who keeps the run of facts, figures and babies, has just laid before an enquiring world the following interesting statistics:

The whole number of languages spoken in the world, amounts to 3,054,587 in Europe, 936 in Asia, 276 in Africa, and 1,264 in America. The inhabitants of our globe profess more than 1,000 different religions. The number of men is about equal to the number of women. The average of human life is about 33 years. One quarter part die previous to the age of seven years; and one half before reaching 17 years of age; and those who pass this age enjoy a felicity refused to one half of the human species. To every one person only one reaches 100 years of life; to every 100 only 6 reached the age of 76, and not more than one live 5,000 live to 90 years of age.”

This short version was published in the Opelousas Courier on January 21, 1854. An example of a longer version of “Interesting Statistics” can be found in the Southern Sentinel, July 23, 1853. Students can locate more examples by searching the historical newspaper database Chronicling America. Additionally, the Viral Texts project uses computer analysis of newspaper databases to explore and map the viral spread of news in the nineteenth century. This map illustrates the newspapers that printed “Interesting Statistics” between 1836 and 1860.

How to Use the Example in the Classroom

First, explore the importance of tracking the source of information and considering the motives of the writers and publishers. Nineteenth-century readers of “Interesting Statistics” would have found it nearly impossible to learn more about this mysterious author. But modern internet search engines open a world of information in seconds. Provide students with an example of modern viral information. Model and practice how to learn more through lateral searches—reading and comparing information across a variety of websites on the same topic.

Next, critically examine the content of “Interesting Statistics” and discuss how popularity does not always equal accuracy. Were 3,054,587 languages really spoken in Europe? That seems unlikely since Europe has around only 100 different languages today. The article notes only 276 languages were spoken in Africa. Really? Modern estimates are 2,000 or more languages in Africa, one of the most linguistically diverse continents.

“Interesting Statistics” was reprinted for at least twenty-four years, from 1836 to 1860. If this demographic information was correct at some point, did it remain the same over that time period? Was it even possible to collect this information from all over the world in the nineteenth century? Why was this article so popular? How might it have appealed to newspaper editors and readers?

Finally, compare the nineteenth-century exchange network to modern electronic media sharing. Locate and identify the types of websites and social media posts that use the electronic equivalents of “Interesting Statistics.” For example, top five or top ten lists of information are a popular format in electronic communication. Why? How are these facts compiled today? What sources are used? Are the sources reliable? What is the purpose of the publisher of fast fact lists?

Comparing and contrasting historical and modern media and asking students to practice media literacy skills as they analyze primary sources provide new insight into “going viral” then and now.

Active Classroom provides hundreds of resources and to practice media literacy.

Try a free 30-day trial today

Cynthia W. Resor is a social studies education professor and former middle and high school social studies teacher. Her dream job – time-travel tour guide. But until she discovers the secret of time travel, she writes about the past in her blog, Primary Source Bazaar. Her three books on teaching social history themes feature essential questions and primary sources: Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries: Modern Lessons from Historical Themes, Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies and Exploring Vacation and Etiquette Themes in Social Studies.