I have wondered, especially this past year, why many Americans dislike their government because they think it intrudes on their freedom, and why many Mexicans and Latin Americans mistrust their governments because they think they are corrupt and abuse their power. How did both societies come to have those specific relationships between the individual and government?

One often ignored cause is the role that religion played in creating government in both societies, a set of events and conditions largely forgotten because Americans generally do not think and talk about religion and government in the same conversations. That is unfortunate, as religion is largely responsible for the type of government developed by different societies. Protestant Christianity in the American colonies of the 17th and 18th centuries was largely responsible for promoting a stronger ethic and practice of self-government than Roman Catholicism did in the Latin American colonies. This is important because it has determined how many Americans think about government today, and this may be different from how Latino students and their families do. This article covers the influence of the Puritans in shaping our government, while this article, Give Students A Fresh Perspective on Government: How Catholicism Shaped Latin American Regimes, examines the ways that Catholicism influences form of government.

Explore U.S. history and government activities in Active Classroom: get a free 30-day trial

The Puritan Experiment: A mix of religion, economics, and government

While government, the economy, and religion are largely seen as separate today, throughout history they have been deeply intertwined. In 1629, nine years after the Mayflower Compact and the establishment of Plymouth Colony, King Charles granted a charter to a group of merchants seeking to establish a trading colony in New England. Most of the stockholders were Puritans. Intertwining economic motives, religious beliefs, and governmental principles, the incorporated Massachusetts Bay Colony was declared a place where Puritans would live under “godly rule.” Under the royal charter, the colony’s stockholders had the sole authority to create a government for the colony.

While government, the economy, and religion are largely seen as separate today, throughout history they have been deeply intertwined. In 1629, nine years after the Mayflower Compact and the establishment of Plymouth Colony, King Charles granted a charter to a group of merchants seeking to establish a trading colony in New England. Most of the stockholders were Puritans. Intertwining economic motives, religious beliefs, and governmental principles, the incorporated Massachusetts Bay Colony was declared a place where Puritans would live under “godly rule.” Under the royal charter, the colony’s stockholders had the sole authority to create a government for the colony.

An emphasis on “the congregants themselves”

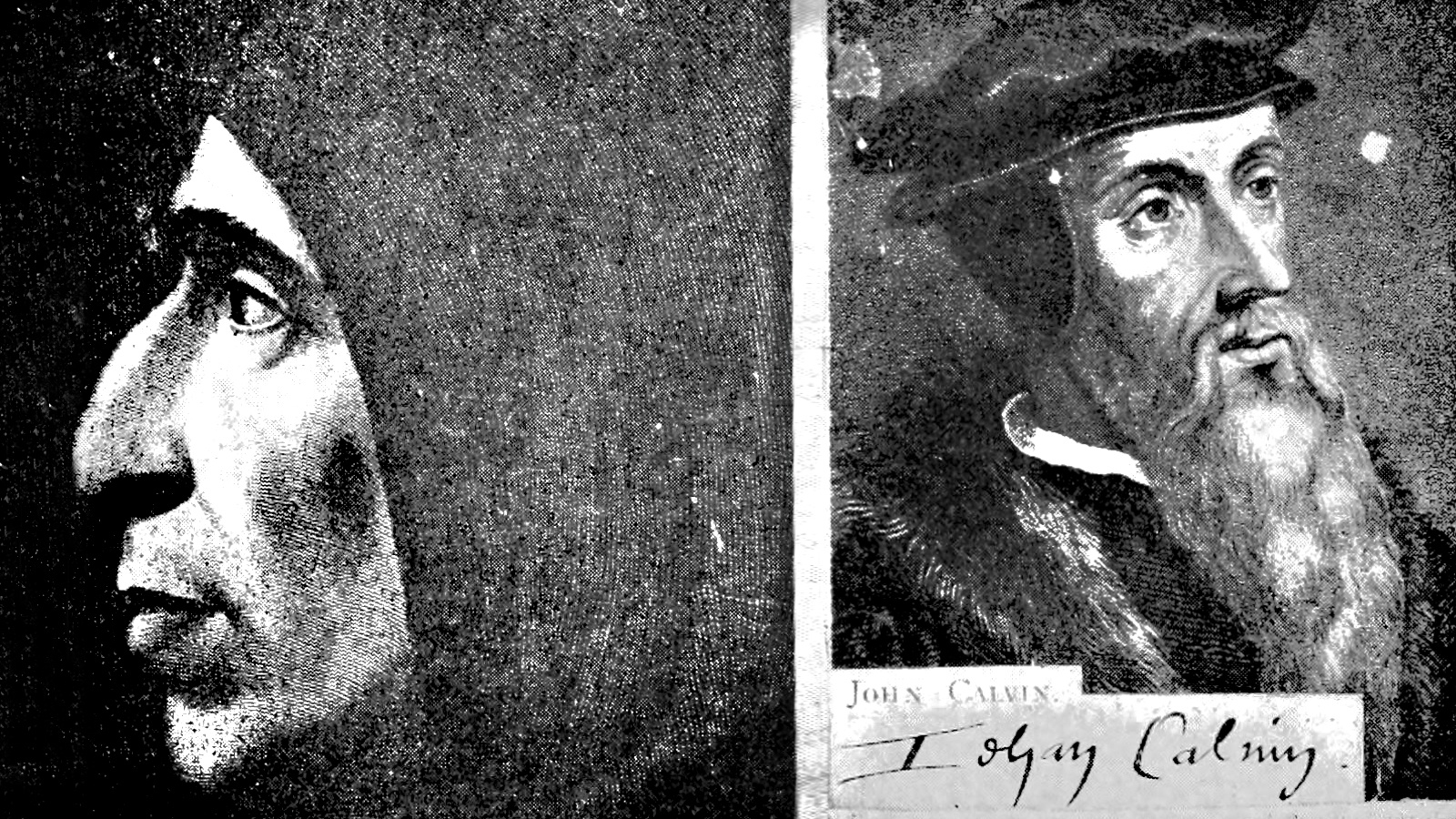

History reveals a variety of reasons why government and religion were so closely linked. For the Puritans, self-rule was how they practiced religion, a direct legacy of Martin Luther’s intellectual declaration of independence from the Catholic Church, one which evolved into the war of independence that was the Protestant Reformation. Each group of Puritans, separated from others only by geography and distance, was a “covenant community” pledging to obey the laws of God. Each congregation elected its own minister and established its own regulations and policies (CRF, 2013). This was in marked contrast with the hierarchy of bishops of the Anglican Church of England, who were elected and appointed by other clergy, a hierarchy closely resembling the organization of the mother Catholic Church. John Cotton, the preeminent minister and theologian of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, “declared that the authority of the church should be congregational, not episcopal; the highest human authority is neither king nor archbishop but the local minister and congregants themselves (Gaustad and Schmidt, 2002, p. 53). This emphasis on “the congregants themselves” shows the developing importance of individualism and self-rule.

Aside from a spiritual point of origin, there was an academic point of origin for these traditions of self-rule. The formative education and training grounds of many Puritan leaders had been at England’s Oxford and Cambridge universities, each of which had developed as a federation of independent, self-governing colleges, houses, and halls, each multidisciplinary and autonomous. In essence, Puritan leaders had been educated and trained in self-rule and self-government, both intellectual and religious, before they ever set foot in America (Beale, 2000, pp. 203-212).

Was Puritan self-governance a theocracy or a democracy?

While the Puritans believed in a separation of the church from the state, they did not believe in a separation of the state from God (CRF, p. 3). The “governed” who were eligible to vote to give their consent to be governed were the “Freemen”—all members of the various Congregational churches.

Individual congregations gathered in a church, also called a meetinghouse, “the center not only of ecclesiastical life but also of social and political life in the seventeenth-century New England town” (Gaustad and Schmidt, p. 60). In the original Plymouth Colony, it was at once the first fort for defense (a cannon from the Mayflower was mounted on its roof), a church for worship, and a meeting-place to conduct the colony’s business, “the center of both the civic and religious life of the little colony” (Addison, p. 87, 1911). This and similar buildings served to call each congregation for religious worship, but also for civic purposes: organizing a militia, building infrastructure, settling disputes over land and property, etc.

The legacy of the Puritans: Distrust of large institutions that “play God”

The Puritan experience was a unique synthesis of religion and government that became a hallmark of the relationship between the government of the United States and the American people: a belief in God as the chief higher power, coupled with distrust of any large institution that wanted to play God, be that the Catholic or Anglican or any other Church, or a monarchy, or a “big” government. The chief principles were to become independent from religious or secular hierarchy and bureaucracy, and authority over the individual. These principles led to self-rule and self-determination—the individual separate from the group, from the collective. This was essentially taking the legacy of Martin Luther and turning it into a clear relationship between people and their government.

Subscribe to the blog to get more articles like this one sent to your inbox each week.

The beginnings of modern conservatism and opposition to “big government”

Within this distrust of institutions were the beginnings of that component of the modern conservative view of government that is opposed to a “big” government perceived as interfering with and controlling the life of the individual. The root of that relationship between the individual and the state was the colonial relationship between the individual and the local church. It was on the foundation of their religious beliefs that the Puritans built their government institutions, a powerful legacy that was to inform, several decades later, the building of the government of the United States. Providing your government class with this kind of background on how religion influences modern conservatism can make different political perspectives clearer for many students.

A different historical legacy

The Puritan perspective may be closer to the view of government held by the half of America which identifies with a conservative view of government, and/or leans toward the modern-day Republican Party, and/or which voted for President Donald Trump.

But the 64% of Latino registered voters who identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party, as found in 2016 by the National Survey of Latinos conducted by the Pew Charitable Trusts, may have a different view of government. This view sees the relationship of the individual to authority and government in a different way, and interestingly, is also greatly influenced by religious history. To find out about how Catholicism influenced a different view of government, read my article, Give Students A Fresh Perspective on Government: How Catholicism Shaped Latin American Regimes.

References

Addison, A.C. (1911). The romantic story of the Mayflower pilgrims: and its place in the life of to-day. Boston, MA: L.C. Page & Company.

Beale, D. (2000). The Mayflower Pilgrims: Roots of Puritan, Presbyterian, Congregationalist, and Baptist Heritage. Greenville, SC: Ambassador-Emerald International.

Constitutional Rights Foundation (2013). “Puritan Massachusetts: theocracy or democracy?” Bill of Rights in Action. Fall 2013, 29:1, pp. 1-5.

Fuentes, C. (1992). Chapter 3: “The Reconquest of Spain,” in The Buried Mirror: Reflections on Spain and the New World. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Gaustad, E. and Schmidt, L. (2002). The Religious History of America: The Heart of the American Story from Colonial Times to Today, Revised. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, A division of HarperCollins Publishers.

Moguel, D.L. (2016). “How Do History and Religion Affect the Reading Habits and Practices of Latino Students?” Occasional Papers, Social Studies Review, 4(3), 1–14, California Council for the Social Studies.

Paz, Octavio (1979). “Mexico and the United States,” translated by Rachel Phillips Belash. The New Yorker, 136–153, 55/31, 17 79, September 17.

Pew Research Center (2016). “Democrats Maintain Edge as Party ‘More Concerned’ for Latinos, but Views Similar to 2012.” National Survey of Latinos. Washington, D.C.: Pew Charitable Trusts. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

Explore U.S. history and government activities in Active Classroom

Get a free 30-day trial today

David L. Moguel is a professor of teacher education at the Michael D. Eisner College of Education, CSU Northridge. He holds degrees from Stanford University, the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, and UCLA. David served as a John Gardner Public Service Fellow with Ramon C. Cortines, school superintendent, and as a presidential management intern for the U.S. Department of Education. He is the co-author, with Ron Sima, of Teach Me, I Dare You: Taking Up the Challenge of Teaching Social Studies, published in 2011 by Social Studies School Service.