Are you searching for ways to make your social studies lessons relate to the lives of your students? Make memorable connections between national trends in history, economics, culture, politics, and geography with these place-based primary sources.

Subscribe to the blog to get more articles like this one sent to your inbox each week.

1. Historical issues from your local newspaper

Many local newspapers are digitized and searchable either through your local library or the Library of Congress. Some databases are accessible by subscription only; others are free. Check with your school or public library to learn if they provide free access to newspaper databases. The Library of Congress’ Chronicling America is a searchable database of newspapers from 1789-1963. The site also includes a directory to learn what newspapers may have been published in your community since 1690.

Many historical newspapers, especially small local papers, have not been digitized. Accessing old issues may require a microfilm reader–an old-fashioned technology predating the Internet era. Using a microfilm reader is more challenging than online, searchable databases, but the experience provides insight into how changing technology impacts the work of historians — the results are worth it!

Local people and events emerge from the pages of local newspapers, giving new insight into the history of a community. National events impact local communities in different ways. The local view of national issues may contrast with the narratives presented in textbooks.

Photo: Library of Congress, Chronicling America series

Choose a national event or trend described in your textbook (such as the Roaring Twenties, Prohibition, or the New Deal) and ask students to explore local coverage from key years. The results may be surprising. For example, flappers never appeared in newspapers of my conservative, rural community in the 1920s, except in movie advertisements. However, stories about bootleggers and people illegally making or selling alcohol were common even before Prohibition began.

Historical newspaper advertisements, comics, and advice columns are often as interesting as the news stories themselves, each providing insight into changes in technology, roles of men and women, and daily life.

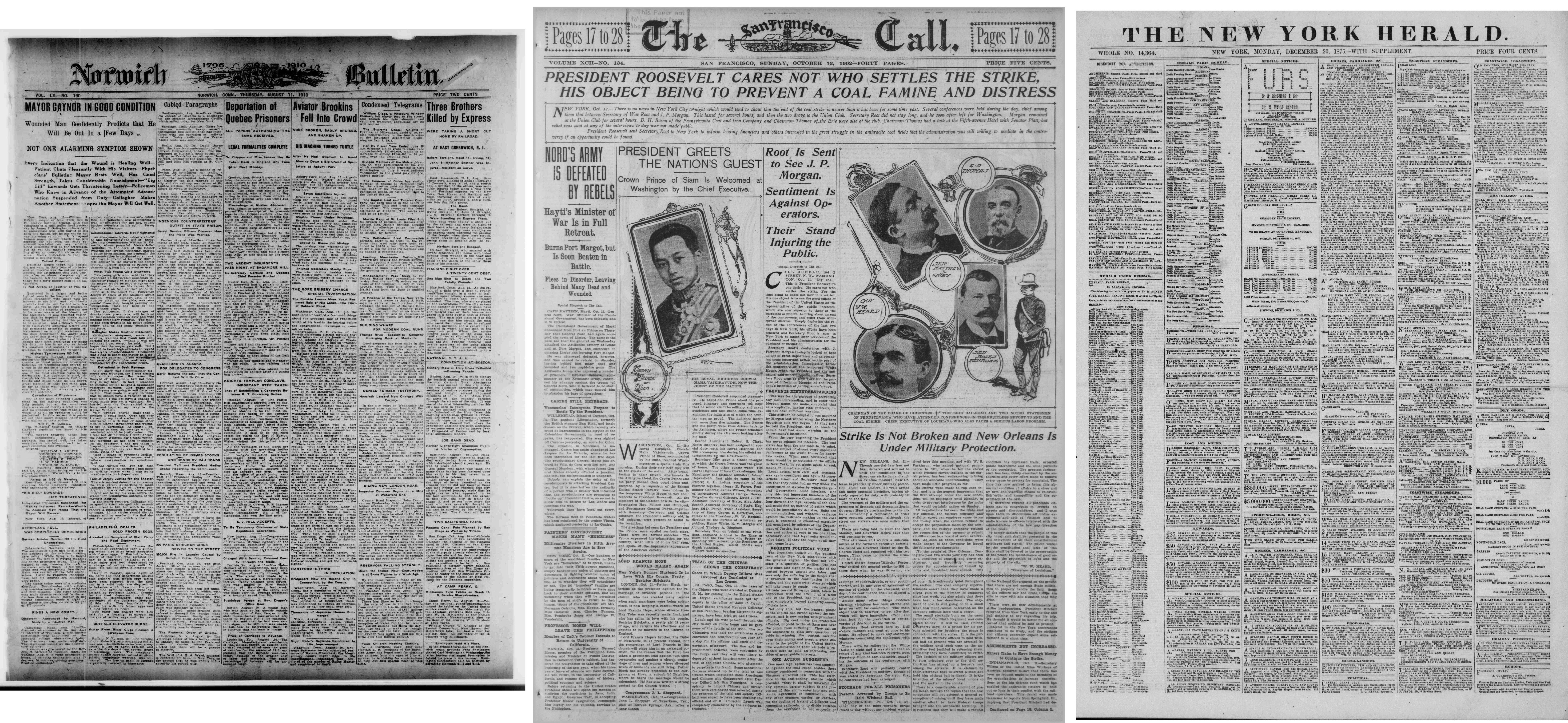

2. Sanborn Maps

Sanborn maps were created to assess fire-insurance liability in towns and cities in the United States from 1867 to 2007. These maps provided detailed information about business, streets, homes, and communities. With a little searching, you can find Sanborn maps for your town. Check the Library of Congress collection or your state or local historical society.

A comparison of maps over several decades reveals how communities grow and change. Houses and buildings appear and over time are adapted for new purposes, or are torn down and replaced. Livery stables and wagon-yard businesses disappeared as motorized vehicles became common. City blocks of factories or other industries developed, declined, or shifted to another part of town as the economy and transportation routes changed. For example, a large distillery was located on the outskirts of my small town before Prohibition. Today, its existence has been forgotten and no visible remains can be detected in the empty pasture where it stood. Sanborn maps provide the evidence for students to consider the impact of economic and regulatory changes on their hometown.

Photo: Library of Congress

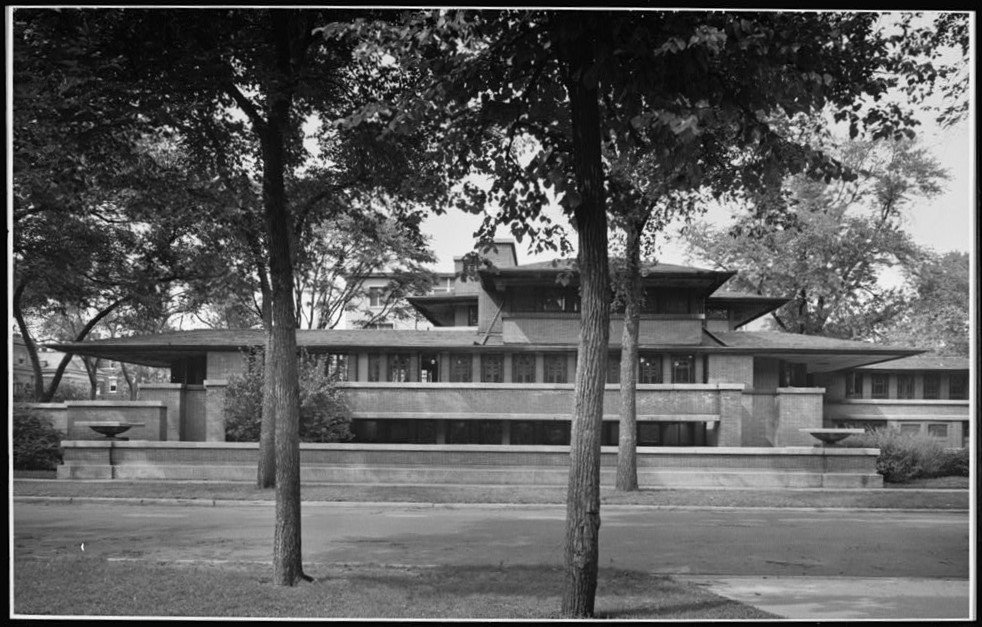

3. The natural and cultural landscape

While Sanborn maps provide a starting point for community exploration, they also are a jumping-off point for students to dig into another primary source–-the natural and built environment of a local neighborhood. First, discover how the natural landscape appeared to early settlers. For example, streams were often diverted or disappeared as communities grew. Hills were leveled, valleys filled. Ask how and why the natural landscape was adapted and changed as the community grew.

Next, examine the cultural landscape: the buildings, roads, and other features created by humans. Which structures are the oldest, the newest? How have their uses changed? The National Register of Historic Places and associated state historical preservation offices gather information and officially list buildings, sites, and neighborhoods worthy of historic preservation. The Historic American Buildings Survey also documents the American cultural landscape. Search the databases, locate nearby properties, or identify new landmarks worthy of preservation.

4. Oral histories

Many digitized oral history collections are available through the Library of Congress and your state or local historical society. Search for examples from your region or local community. Students can also create their own oral history projects by interviewing relatives and friends. At the end of instructional units on the 1960s, 70s, 80s, or 90s, ask students to brainstorm a list of the most important events of that era. Teach students how to exercise their critical-thinking skills by asking them to write quality questions, and then interviewing older generations about their memories of these national events. Students learn that individual memories of pivotal national events and trends vary. Students should then compare and contrast individual memories to the accounts of historians and textbooks.

5. The archives of your local historical society

If you haven’t visited your local historical society, go today! Even better, take your class to learn how primary sources are collected, preserved, and studied. Many wonderful local primary sources have never been digitized. The historians, archivists, and librarians are usually thrilled when teachers and students are interested in their primary source collections. Seeing these in person will give your students a new perspective. They will discover new things about their community and learn how historians do their work.

Access hundreds of primary source activities

Try a free 30-day trial of Active Classroom

Cynthia W. Resor was a middle and high school social studies teacher before earning her Ph.D. in history. She is currently a professor of social studies education at Eastern Kentucky University. She is the author of a blog, Primary Source Bazaar, and two books on teaching social history themes using essential questions and primary sources: Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies and Exploring Vacation and Etiquette Themes in Social Studies.