Did you miss this webinar? Now you can read all about it. Below is an easy-to-scroll transcribed webinar of “Tools for the Elementary Classroom: Evaluating Primary and Secondary Sources,” which was hosted by Melissa Knowles and moderated by Jessica Hayes on February 3, 2022.

This webinar can be used to support elementary social studies, teaching primary sources, meeting C3 inquiry social studies standards, and building student analysis skills.

Jessica Hayes (JH): Welcome, everyone! Thank you for joining us for today’s webinar. I am your host, Jessica Hayes, and we are joined today by our presenter, Melissa Knowles. Melissa and I work together for Social Studies School Service, so I’m very excited to be her host today. She builds curriculum maps and trains educators on using the various programs, and she also develops microcredentials.

Melissa Knowles (MK): Thank you so much, Jessica. I am so excited to be with you today. My name is Melissa Knowles. I have a BS in elementary education and a master’s and educational specialist degree in library media. I’ve been in education for eighteen years now. I have actually taught several elementary grades, kindergarten, fourth, and fifth. I’ve taught all of the elementary grades as a librarian, all the way up to eighth grade. So I have got a pretty good experience level with different types of students. I am currently a library media specialist and a K–6 virtual teacher.

I’m really having a busy year, to be honest. I also am a technology coach. I absolutely love technology, and I am a certified facilitator for Social Studies School Service on all of their products. So I’m really excited to be here with you today because I am using these primary secondary sources in my library with my students.

Let’s go ahead and get started. We are going to talk about our objective, or what we want to get out of this session. We’ll talk about content, we’ll close, and then we’ll have some time for questions and answers.

Today I want to work with you to

- discover ways to access primary sources as well as secondary sources in the early grades; and

- explore methods or techniques for integrating the evaluation of sources in your classroom.

I want to make it as easy as possible for you to bring sources into your classroom and use them with students.

And I hope you will have some lesson ideas—activities, really—to enhance social studies and the use of primary sources in your classroom starting as early as tomorrow.

Primary sources provide firsthand evidence about the people, events, or phenomena you’re researching.

Primary sources will usually be the main objects of your analysis. I like to take anything possible—firsthand evidence, firsthand primary sources—directly from the students, whether that’s photos, writing, or things that they have created. It seems to really be an easy way to bring primary sources in and to introduce them with my students.

Secondary sources are important for students, whether it’s a researcher writing about somebody else or maybe a biography as opposed to an autobiography.

We discuss these differences, and we even have the students talk about themselves with a partner and then the partner talk about that student, and we just look at the difference. If you’re using secondhand sources, information may not quite be as reliable as with primary sources. We do a lot of this with students while we’re reading in the library and while we’re investigating different topics.

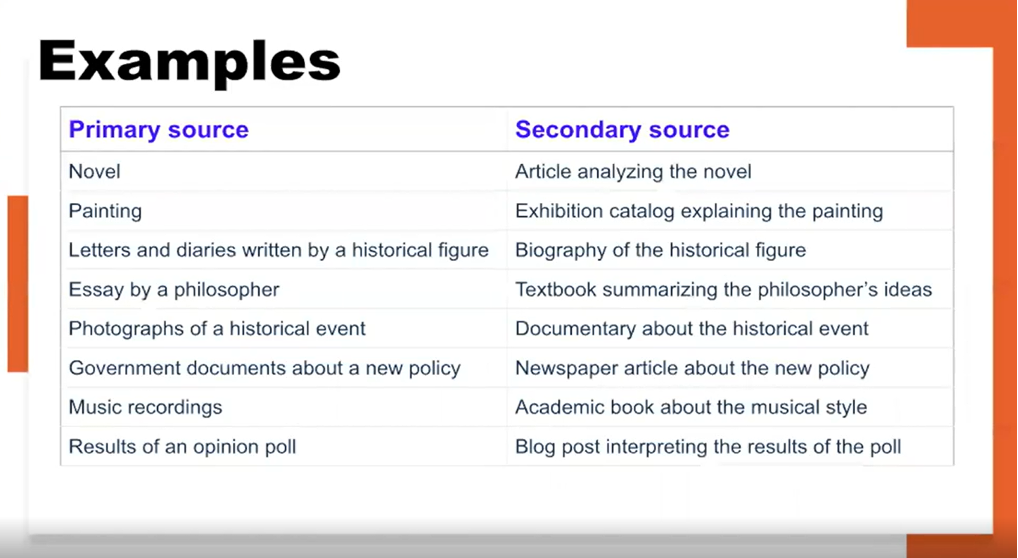

I like this chart:

It gives a primary source, and then it has a secondary source option for that. So, for a novel, maybe it’s an article analyzing the novel or a review of the novel; for a painting, it’s a catalog; for letters or diaries written by a historical figure, it’s a biography of the historical figure. I think this is a really interesting way to bridge these two things because this is something we’re going to have to teach explicitly to our elementary students as they begin.

Let’s say your students did not get any instruction on primary/secondary sources in the previous years. You can start basically at the same level. It doesn’t matter what grade you teach; you can start the same way. Your resources and topics may look different, and what you get from the students may be a little bit different, but we can build and begin the same way.

Now I want to ask you a question: Are primary and secondary sources essential to your students?

JH: I have some responses, Melissa:

- “I say yes because it allows them to make their own interpretation of an event.”

- “Absolutely essential. Otherwise, we cannot teach them to use historical-critical thinking skills. They can think like historians.”

- “Yes, students need their connection in order to stir interest in the topic. Sources can provide the wow that we hear so much about in other subjects.”

MK: Woo, that’s awesome. Great job. So let’s talk a little more about that, and then maybe we’ll revisit this question a little bit later. Primary and secondary sources can be a little bit daunting. A lot of that, I think, comes from teachers not being sure how to use them and where to find them. And maybe they don’t realize, as you guys do, the importance of these primary sources for students and of their being aware of what primary and secondary sources are.

We all know that primary and secondary sources are of value at our grade level. That is not going to be questioned here. But what do primary sources do for your students?

They expose them to multiple perspectives. Not everybody thinks the same way. And it’s important for students to realize how other people think, even if it’s just them analyzing an image differently.

But we know that history and things that have happened in the past are extremely debated. Not every person really agrees on exactly what happened. With primary and secondary sources, students get those multiple perspectives and can become part of the debate. They have a source—evidence—to support their thinking.

They also help students develop those analytical skills that we want them to develop by engaging in asking questions, thinking critically, making intelligent inferences, and explaining their reasoning. They are also excellent for developing critical thinking skills.

Primary sources are snippets of history; they’re just these little incomplete, often out-of-context sources that require students to think a little bit deeper, examine thoughtfully, and determine what else they need to know in order to make great decisions or develop their ideas on what is happening.

Also, all history is local. History is not something that happened way far away or a long, long time ago.

History is happening all the time. And so it allows students to tell their story, too, and to realize their history and how their history connects with history around the globe. It really gives them a sense of world history and their personal family history together.

It also helps students empathize. Maybe a student has not had a certain experience, but they can relate to it because they are a child or they are a child that relates to that person in some other way. And so they get a deeper understanding of what happens in the world based on their understanding of that person or some connection that they have with that person. They’re going to get several different points of view. And in analyzing primary sources, students move from those concrete observations and facts to making inferences about the material.

Point of view is one of the most important inferences that can be drawn. What is the intent of the speaker or the photographer? What is their interpretation of it? How does that help them understand and provide evidence for their thinking.

It’s also difficult for students to understand that everybody participates in history every day. We all create primary source documentation all the time, probably even more now with all of the technology. But they can examine the past in the first person. It really brings history into their world and makes their understanding a lot more concrete.

These are some things that I think are really important in addition to the things that you guys suggested.

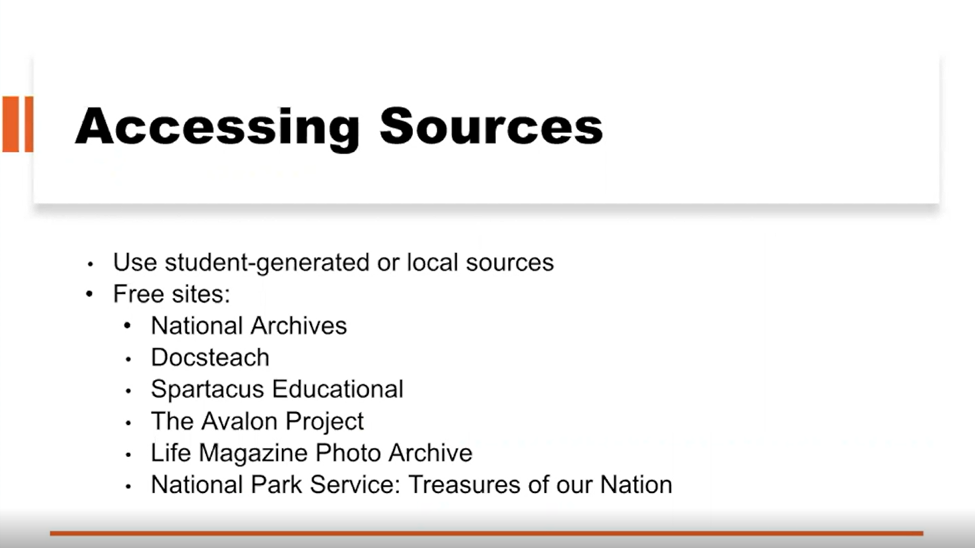

Let’s look at how we can find sources. These are a few of my favorite sites:

Number one is student-generated or local sources. That is because I deal with a very young clientele on a daily basis. As much as possible, I like to use things they have created and things that are happy in the world around them directly related to them. Then, as you get into the upper elementary grades, these free sites are awesome too. You can do a Google search for any of these and find some great resources. And there are so many others out there.

How do I start with primary sources in my classroom?

The first thing is building background. It’s very important that students have some sort of understanding, some sort of connection that they can make to whatever primary source they’re looking at. I like to use a lot of compare and contrast. I’ve given students different types of sources and had them sort them into images, newspaper articles, and different things just so that they can really get an understanding of the types of primary sources because that builds us straight into understanding why we would use different types of sources. What kind of source would we need to find information on this?

And then scenarios are fun, and you can find some of these on the internet. I found this one: “I was watching the Disney Channel, and one of the reporters said I should see a movie she really liked.” When she talks about the movie, what is she? Is she a primary or secondary source? Giving them some scenarios can be real life. They’re quick things that you can do as students are lining up or in those five minutes you have.

The second most important thing is to model, so the first thing I do is walk through this with students myself.

I observe, reflect, and question primary sources before releasing them to the students. Then we’ll do it together in small groups, then shoulder partner before we move into a pair-share individually. They can still hear what everybody is saying before we really move into more of a one-on-one conversation. And then, of course, hopefully, we eventually get to them being independent.

We’re going to begin with the simple steps, build vocabulary and comfort with the task of observation. Choose your primary sources carefully. We want to start with primary sources that have plenty to talk about, something that they’re definitely going to have some familiarity with, some connection with, even without a whole lot of back instruction. You can even choose primary sources that have a little dispute to start with, where you think, “Oh, I’m going to have students on different sides of this.” You can add some ambiguity for higher-level discussions as students become more comfortable with the process. So not only are you releasing out to students, but you’re asking deeper questions or providing sources that are maybe a little bit harder to analyze.

You can also add some props to make the experience more authentic!

You could have students use magnifying glasses. Something fun to really make these primary sources seem more authentic is to get white gloves like they would use at the archives. The magnifying glasses that I use actually came in a science kit, I think. This observation phase becomes not just looking at a picture and saying stuff but something more serious when you’ve got gloves and magnifying glasses out. We even do this with adults, and they love it.

Start with teaching the process and then repeat the practice so they’re observing. “If I show you a picture of a farm, what would be some typical farm animals you might see?” The students are going to say different animals, and as they’re talking, you say, “Oh, well, I heard someone say that you’ve maybe heard a certain sound. What made you think of that animal specifically?” Or just asking more open-ended questions can really help: “Silently store three things in your head that you see and then share.” It really gives students an opportunity to be a part of the discussion and then go, “Oh, I see what you saw.”

Maybe you need to pull them out a little bit more as they’re observing: “Can you point to that?” “What makes you think about that?” Maybe there are some clues in the picture that make them come to a certain conclusion that’s not exactly depicted in the picture.

This process is nonlinear. That means you do not have to observe, reflect, question, observe, reflect, question. When I’m observing, it gives me some reflection. I may ask the why while I’m observing. It doesn’t necessarily have to be one and then the other. It can all happen at once.

Sometimes I’m like, “Why are they doing that? I don’t understand what’s happening there.” Some images can cause students to really have a reaction or not to really think deeply, like if they see a cute baby or puppy. One of the goals here, remember, is for learners to look at the details of the image and determine why they reacted a certain way. “Why do you think that is cute?”

You want to ask students something like those five W questions:

“What is happening in this image?” “What do you see?” “Who are the people in this image?” “What suggests that that is who they are?” “Where do you think this is a picture of, and what helps you think that?” “Where was this picture taken?” “Why do you think that?” “What do you see in the picture to help you decide these kinds of questions?”

You’re really pulling students in, pulling that information out about the reasoning. You can even do some comparing and contrasting with your question by saying something like, “If someone took this picture today, how might it be the same, or how might it be different? What clues do you see?” As you’re asking these types of questions, the students are getting more practice. They’re automatically going to then start thinking this way, and so it’s going to become more natural for students to start thinking about these questions on their own, and then they can test their ideas and hypotheses with the next step: questioning.

I like wonder because it seems less structured than questioning. “What do you wonder about this image, and what questions do you have?” That seems just a little bit more positive for students. They might wonder what kind of farm animals there are in other biomes or in Africa, what they would have on a farm rather than necessarily what we have here in our local environments.

When we get to this point in primary sources, the goal is for students to want to learn more. The wondering and questioning should lead to more observations and reflections, especially in the group.

It’s much easier than individually because they sort of piggyback on each other: “Oh, I was thinking that too” or “I see what you’re saying.” You’re getting a lot of feedback from the students, and it really gives good prompts to their thinking: “What do you wonder about after looking at this image?” “If you could ask a person or animal in this picture a question, what would you ask?” That has been a fun question to ask my students, probably one of my favorites, because you’ll get some silly things, but then you’ll get some really interesting deep thinking.

It’s interesting what students of different ages and backgrounds come up with, and it tells you a lot about the students. What more do we need to know in order to answer our big question? I encourage you when you do put a primary source such as this one out to have a big question ready for students, an inquiry guiding something that you’re trying to discover, even if it’s just related to whatever topic you are learning.

This is a picture of a classroom in the past. You could have students compare and contrast the classroom, compare and contrast the students, set the date.

“When do you think this would have happened? And what is your reason why you think that?” I think the more primary style is coming back a little bit, so it may be confusing to students, but maybe the style, all of the furniture, or other things in the image could help them in their questioning. “Do teachers look like that? What about the wall? Do we use chalkboards?” You’ve got a lot of different things that the students can observe, but what I like is after they observe the stuff on the surface, they really start to get into “I wonder what they’re doing. Are they doing a math activity? Are they counting? What are they creating? Is this an art? What are they doing?” Discovering and asking different questions about an image really builds more learning, and these are some easy ways to bridge primary sources and secondary sources at any time during the school year.

Now, what about this image based on clothing?

“What would the environment and weather be like?” “Compare and contrast toys, clothing.” “Where do you think they are, in a big city in a rural area?” You’ve got a lot of ways that you can go with this. You can even give it to students and just see what they come up with. That’s why I like to give them just a number: “Find three things that you observe. Point to one that you want to share.”

What about this comparison?

“Compare and contrast the two ships. Which one would you want to be in? Which one would feel safer?” “Talk about ways things can move, like wind engines.” “Talk about why these ships might have moved in different ways.” “What is the weather like?” “How did it feel to be on a ship with waves like that?”

When you are working with primary and secondary sources in your classroom, you are allowing students to be historians. You’re allowing students to really engage with history in a way that they can relate to.

They’ve seen boats. You’ve talked about boats during the school year with the different explorations that we talk about every year. They know about schools; they know about toys and kids. These are all things that any age group can relate to. But the real key is just an opportunity to practice. If you’re giving students primary sources, you’re giving them opportunities to observe, to reflect, and to question on these primary sources. That is the key because that’s going to really build their inquiry, their understanding, their ability to question and analyze. Because they’re getting practice. They’ve seen you do it. They’ve heard other students work with this, and they’ve been a part. So automatically their knowledge level has increased, and hopefully they do not feel that when they look at a picture, their mind just goes blank. Which is another reason that observation is a great place to start, because everybody can see something.

Q&A with Attendees: So do you have any questions?

Attendee: Do you have a database of resources that you’d be willing to share? We’re redesigning our social studies curriculum, so any leads will be helpful.

MK: Do you have Active Classroom, by any chance?

Attendee: No. I’m the director of teaching and learning, so I’m helping ten grade levels really think about their social studies curriculum.

MK: What state are you in, California?

Attendee: Yes.

MK: We recently did some California maps with Active Classroom, and I know you could get a thirty-day trial, and the reason I’m suggesting that is because almost 100 percent of the activities in Active Classroom have primary sources. So I think that would be a neat place for you to start, and it’s a great resource because it would literally be a full curriculum.

I do want to tell everybody, thank you so much for being here tonight. Thank you for taking the time to learn a little bit more about primary sources and secondary sources used in your classroom.

JH: I want to go ahead and just tell everybody thank you for joining us too. We here at Social Studies School Service really appreciate you letting us be a part of your ongoing professional learning. Thank you, Melissa, for sharing your expertise with us. And I hope everyone has a great evening!

Active Classroom has hundreds of primary source activities to build critical thinking in the social studies classroom

Try a free 30-day trial today

Transcription has been edited for clarity and length by the team at Social Studies School Service. Watch the full webinar here.