The United States has been involved in trade wars with nations around the world in recent years. Instead of weapons, these “wars” are waged with tariffs, taxes on imported or exported goods.

However, trade wars among nations or empires seeking to protect their economic interests are not a new thing. Use the following four historical examples to demonstrate how commercial interests are often at the heart of international armed and unarmed conflicts.

Punic Wars: Trade War in the ancient world between Romans and Carthaginians

Carthage, an ancient city located in North Africa (in modern Tunisia), controlled a vast trade network that included parts of Spain and the islands of Sicily, Corsica, and Sardinia. The Carthaginian navy protected their trading ships throughout the Mediterranean Sea. The Carthaginians exported agricultural and food products such as grain, fish sauce, figs, and olives as well as metal, manufacturing goods such as cloth and jewelry, and slaves.

By the mid-200s BC, Rome controlled most of the Italian peninsula, but their expansion in trade and territory was limited by the power of the Carthaginians. The Romans knew new territories meant lucrative economic markets for and new revenues in the form of taxes. Rome and Carthage fought a series of military campaigns, known as the Punic Wars (264-146 BCE). Ultimately, Rome won on the battlefield and the city of Carthage was destroyed. However, in the years that followed, the city was rebuilt by the Romans and become one of the largest cities in the Empire, supplying goods throughout the Roman-controlled Mediterranean.

Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) – Religious or economic motives?

The Fourth Crusade began like previous crusades with a pope calling for military action to capture Jerusalem. At the time, Jerusalem was controlled by the Islamic Ayyubid Sultan of Egypt and Syria. However, the Fourth Crusade turned into a war waged to dominate markets in the eastern Mediterranean. The Italian trading city of Venice funded ships to transport the crusaders, hoping to gain trading rights and an advantage against their economic rivals in Italy such as Genoa, Pisa, and Amalfi. The Crusaders were unable to pay the Venetians for transport to the coast near Jerusalem. So, they “paid the bill” by threatening Christian cities along the Adriatic coasts and capturing Zara, a valuable commercial port, for the Venetians.

The next target for the crusaders was Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire and Venice’s major commercial rival outside of Italy. Crusaders sacked the city and divided the proceeds with the Venetians, helping Venice increase their wealth and power in the subsequent centuries. Ironically, Christianity was the official religion of Constantinople. The Europeans never even made it to Jerusalem.

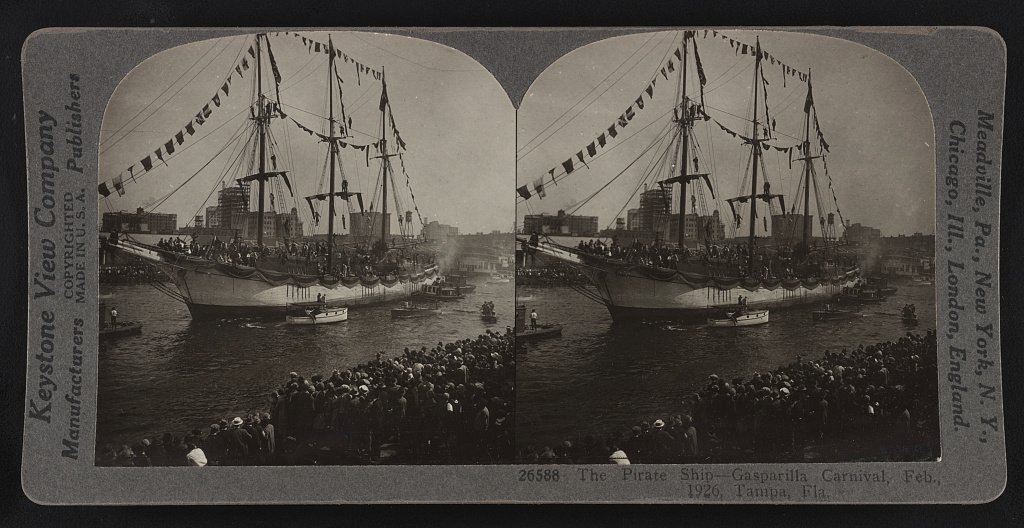

The Golden Age of Piracy (17th and 18th centuries)

Pirates may be portrayed as independent adventures in modern media, but in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, most were officially authorized by a government to attack the ships and confiscate the goods of trade rivals. Most European nations and the United States issued these “letters of marque” which made piracy legal. The privateers, or pirates, were required to submit the captured ships and goods to an official court. The court sold the ship and goods at auction, kept a portion for the government, and rewarded the privateers with the remaining profits. Spanish ships transporting gold from their American colonies were especially popular targets in these trade wars.

Opium Wars (1839-1860) – War over trade deficits

The Opium Wars in the mid-nineteenth century were trade wars between the British Empire and the Chinese emperors. For decades the armed conflict began, Chinese products such as tea, silk, porcelain, and tea were in high demand by British traders. However, the Chinese government limited foreign trade and imports and weren’t that interested in the products the British offered in exchange. The British were frustrated by this trade imbalance or deficit. In the late 18th century, the British discovered opium produced in their Indian colonies was a product the Chinese did want to buy. Britain and other western nations began illegally importing opium into China. As more and more Chinese became addicts, the British trade deficit with China began to reverse. When China cracked down on the illegal trade of the drug, the British responded with military action. In the end, European powers were allowed more and more rights to trade in China.

Modern trade wars are far less violent than these historical examples, but the raw materials, agricultural goods, and manufactured products involved now are not so different. Private profits and government revenues are often at the core of foreign relations, in the past and during our modern times.

NOTE: To adapt any of these historical themes to remote learning, we recommend utilizing this blog content in conjunction with online curriculum resources and lessons from Active Classroom, Nystrom World, or the Library of Congress. This blog can be sent to students to provide context for remote world history assignments or long-term economics projects revolving around tariffs and trade

Make history and economics come alive in the classroom with simulation-based learning

Cynthia W. Resor is a social studies education professor and former middle and high school social studies teacher. Her dream job – time-travel tour guide. But until she discovers the secret of time travel, she writes about the past in her blog, Primary Source Bazaar. Her three books on teaching social history themes feature essential questions and primary sources: Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries: Modern Lessons from Historical Themes, Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies and Exploring Vacation and Etiquette Themes in Social Studies.